Speculative Realism

Frank Thirion

Frank Thirion 'Ganguru Synthetica I' (after George Stubbs), 2025 Ganguru Synthetica I turns a watchful eye back upon the very act of looking. At first glance, the portrait recalls George Stubbs’ 18th-century painting of the kangaroo — itself a construction, imagined from incomplete descriptions and colonial fantasy. Yet Thirion’s kangaroo is not merely an homage; it is a new apparition. The creature’s gaze is lucid, its fur rendered with convincing naturalism, but the surface is interrupted by a drift of squares that shimmer in and out of focus, like fragments of code carried on a digital breeze. This interference is not a flaw but the point. The animal is simultaneously present and unstable, a living body refracted through the logic of machine vision. The flickering grid suggests data packets, scan codes, or compressed pixels — a reminder that this “wild” image is filtered, processed, mediated. If Stubbs’ 'kongouro 'was an invention of colonial imagination, Thirion’s is an invention of computational speculation. Both speak less of the animal itself than of the systems that sought to capture it. The squares remind us that even the most ephemeral of phenomena is now subject to capture, compression, and circulation. Thirion’s art does not mourn this condition; instead, it foregrounds it. By celebrating the “glitches” and artefacts of AI image-making, he draws attention to the seams where imagination, technology, and reality intersect. These interruptions are the hooks that pull the viewer in, forcing us to reckon with the constructedness of vision itself. In Ganguru Synthetica I, Thirion suggests that no image of nature is innocent. From colonial misrepresentations to digital translations, nature is always entangled in systems of power, technology, and desire. What emerges is not a nostalgic longing for purity, but a speculative realism: a recognition that our access to the real is always mediated — and that in these very mediations, a new kind of beauty takes shape.

Frank Thirion ‘Ganguru Synthetica I’ (after George Stubbs) 60x60cm polypropylene water-resistant film, 2025.

Speculative Realism explores how imagination, observation, and technology shape the way we picture the world.

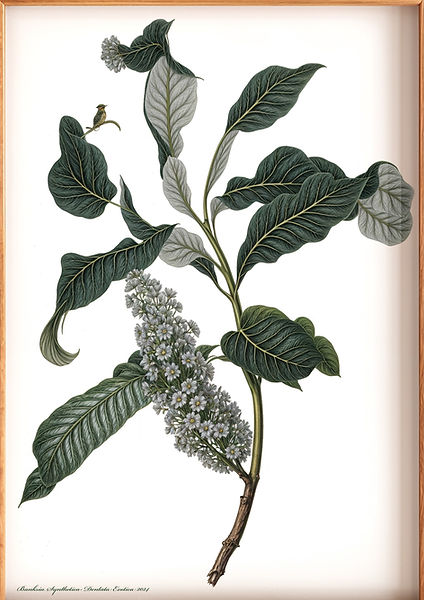

In the 18th century, George Stubbs painted the Kangaroo and Dingo without ever seeing them, inventing creatures from pelts and stories. By contrast, Sidney Parkinson travelled with Cook to Australia, producing hundreds of detailed botanical drawings from life. Frank Thirion revisits these histories through artificial intelligence, creating new “synthetica” Banksias and reimagined animals that blur fact and fiction. Like Stubbs, the AI invents from fragments; like Parkinson, it catalogues with precision. The result is a speculative realm where the familiar becomes strange and the strange, suddenly plausible. At its centre, a short film animates these images into uncanny life, culminating in a kangaroo leaping from its frame. What remains is not the animal, but the landscape — revealed as the enduring subject of a brave new world.

Frank Thirion ‘A Brave New Word 2.0' 60x60cm polypropylene water-resistant film, 2025.

Frank Thirion ‘A Brave New Word' 60x60cm polypropylene water-resistant film, 2025.

Frank Thirion ‘Brave New Word 1' 60x60cm polypropylene water-resistant film, 2025.

Frank Thirion ‘Brave New Word 2' 60x60cm polypropylene water-resistant film, 2025.

Frank Thirion ‘Brave New Word 3' 60x60cm polypropylene water-resistant film, 2025.

1.

Frank Thirion

‘Banksia Synthetica-Dentata Exotica’

(after Sidney Parkinson).

20x25cm polypropylene water-resistant film, 2024.

2.

Frank Thirion

‘Banksia Synthetica-Serrata Exotica’

(after Sidney Parkinson).

20x25cm polypropylene water-resistant film, 2024.

3.

Frank Thirion

‘Banksia Synthetica-Ericifolia Exotica’

(after Sidney Parkinson).

20x25cm polypropylene water-resistant film, 2024.

4.

Frank Thirion

‘Banksia Synthetica-Integrifolia Exotica’

(after Sidney Parkinson).

20x25cm polypropylene water-resistant film, 2024.

1.

2.

3.

4.

George Stubbs

'Kongouro' 60x71cm cm oil on canvas, 1772

Frank Thirion 'Ganguru Synthetica’ (after George Stubbs) 105x87cm polypropylene water-resistant film, 2024

George Stubbs

'Wild dog' 60x71cm cm oil on canvas, 1772

Frank Thirion ‘Canis Lupus Synthetica’ (after George Stubbs) 105x87cm polypropylene water-resistant film, 2024.

Frank Thirion — Mythopoeia and Artifice (2025)

(After Francesco Albani’s Apollo and Daphne, 1620).

A god pursues, a nymph flees — the ancient story of Apollo and Daphne, retold countless times. Here, the artist invites artificial intelligence to reimagine the myth. The scene is lush, precise, almost too perfect: storm clouds brood where Cupid once hovered, Daphne’s spear sprouts prematurely into laurel, and Apollo’s hand glitches, its fingers strangely incomplete. What might have been divine becomes fragile, unsettled, and speculative.

Rather than narrating the myth as we know it, the work suspends us in a moment of uncertainty — Daphne mid-flight, mid-transformation, caught between freedom and surrender. It is a vision both familiar and estranged, reminding us that myths, like images, are never fixed. They live again when retold — whether by painter’s brush or by the algorithms of our own time.

Francesco Albani ‘Apollo and Daphne’ c.1615-1620, oil on copper mounted on wood, 6.8x13.9 inches

Frank Thirion ‘Mythopoeia and Artifice’ (after Francesco Albani c. 1615-1620) 130x50cm polypropylene water-resistant film, 2025.

Mythopoeia

Frank Thirion — Mythopoeia and Artifice (2025) In Ovid’s Metamorphoses, the story of Apollo and Daphne is one of pursuit, resistance, and metamorphosis. Francesco Albani’s delicate copper panel of the early seventeenth century captures the drama as Apollo stretches toward the fleeing nymph, while Cupid hovers above, mischievously ensuring the god’s desire will not be denied. Thirion’s Mythopoeia and Artifice revisits Albani’s composition through the lens of artificial intelligence. What emerges is a vision at once faithful and estranged: myth refracted through digital precision, landscapes sharpened to cinematic clarity, fabrics rendered with impossible sheen, faces smoothed into porcelain masks. Where Albani’s brush breathed softness, Thirion’s AI mediation produces a surface too real to be real — myth transformed into simulation. The title Mythopoeia and Artifice is apt. It names the condition of mythology in our time: no longer the sacred inheritance of culture, but an artifact re-coded, re-framed, and fabricated anew. Myth today is not lived but simulated — dazzling, deficient, seductive, glitching. Thirion’s work stages precisely this confrontation, where antiquity collides with algorithm, where the human drama of desire and resistance is reanimated by a machine that knows neither. What results is a vision both beautiful and hollow, resonant and estranged. Daphne flees Apollo once more, but now she flees into image itself — into the speculative, into the artifice.

Daphne, meanwhile, clutches a spear that already blossoms into a laurel branch. In Albani’s narrative, her metamorphosis comes only at the end; here, it begins mid-flight. Resistance and surrender collapse into a single gesture, the weapon that might defend her transforming prematurely into rootedness. Read today, this blossoming carries a double weight: both ecological allegory, where survival is found in transformation, and a meditation on autonomy, where agency is undone even before capture. The image falters most tellingly at Apollo’s outstretched hand. Rendered with three fingers and a thumb, it is the AI’s error, a moment of rupture in the illusion. Thirion leaves it intact, celebrating the accident as the very hook that catches the viewer’s eye. The deformity weakens the god, diminishes his perfection, and makes visible the artifice of the whole scene. It is in this glitch — absurd, unsettling, unforgettable — that the work locates its speculative power.

The most striking absence is that of Cupid. In Albani’s original, the winged child embodies divine play, the arrow that tips Apollo into frenzy. In Thirion’s version, Cupid vanishes, replaced by storm clouds. Mischief is replaced by atmosphere, play by threat. The story is no longer softened by divine intervention; it is darkened by inevitability. Love, stripped of its playful instigator, becomes pursuit shadowed by menace.